If popular culture is any indication, the last fall's release of "The

Devil's Advocate", with megastars Al Pacino and Keanu Reeves, does

not bode well for any reputational comeback in the fortunes of the

legal

profession. In it, the head of one of the US's most prestigious law

firms

turns out to be none other than the Great Satan himself. The Devil's

legal

persona suggests lawyering as a new metaphor for evil in the 90's. In

fact,

a whole string of recent books and movie hits including John Grisham's

Rainmaker; Jim Carey's Liar, Liar; and William

Deverell's

CBC TV hit Street Legal, suggest that public perception of the

moral,

ethical, and legal values of the profession remains at all time lows.

In

a profession where relationships and matters of trust form a central

element

of competitive advantage, this has to be disconcerting.

But lawyers have long been the professionals that people have loved to hate, so why should now be any different? Right? Well, maybe! Poll after poll has remarked on a declining trend in the levels of public trust and confidence in the profession. And, rightly so, the issue has now moved to centre stage among the concerns of Canadian lawyers themselves, according to an Angus Reid poll for the CBA -- after all, legitimacy is in large measure a product of perception and expectation.

Among Canada's regions, EKOS finds that BC is the most distrustful (60%), followed by Ontario (49%) while Atlantic Canada and the Prairies are the most trustful. Those whose mother tongue is neither French nor English are generally more distrustful of lawyers and, interestingly, young people are more trusting of lawyers than their parents, especially parents who are upper middle-class wage earners ($40K+).

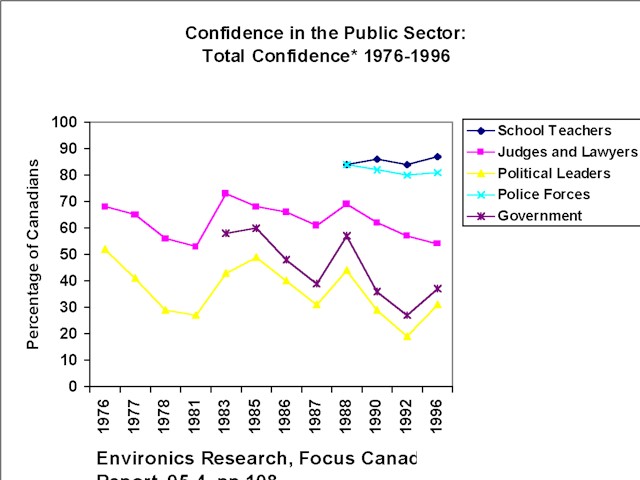

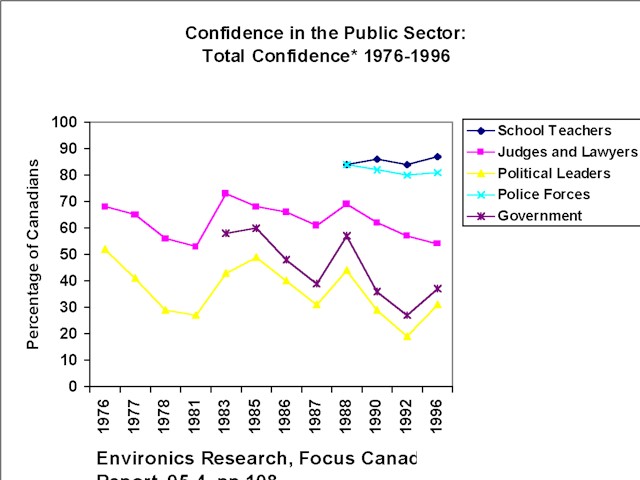

Public trust has also been studied by the Environics Research Group. Their work has tracked public confidence -- a term that implies elements of trustworthiness and elements of faith in professional competency -- in various professional groups for the last 20 years. In the Environics survey published in 1996, only 8% of Canadians express a lot of confidence in judges and lawyers, albeit 54% have at least some confidence. This represents a decline (see graph) of 14% from 1976 when Environics first began gathering data on public confidence and a decline of 19% from 1983 when the profession experienced its highest levels of public confidence. Thirty-five percent of Canadians, on the other hand, have a lot of confidence in school teachers. In fact, the 87% of Canadians that have some confidence in educators is up 9% since 1992. To be fair, the legal profession is not entirely in the dog-house - that place is reserved for our politicians and governments - however, it is the only profession, according to Environics, to experience a steady erosion in public confidence over the last twenty years.

Just as with banking services, legal services could become standardized and commodity-like with less and less need for human contact. Once a commodity, competitive forces will make it harder to justify the personal component of many legal services. To avoid going the banking route, lawyers need to emphasize the fiduciary component of their services which will in large measure be based on their reputation and the level of trust the public holds in the profession.

As the pollster POLLARA emphasizes, gaining and holding on to relationships of trust is a key element of sustaining competitive advantage, particularly for service businesses like the law. In this light, the encroaching trend on legal services by accountants, bankers, and other professionals which was recently highlighted in the National (June-July, 1997), can be partly explained by the fact that these professions experience about twice the level of public trust as their legal counterpart. A combination of market alternatives and low trust could see a ghetto-ization of the profession, making it harder for lawyers to learn from non-lawyers, a process by which lawyers maintain their relevance and market appeal.

Low trust also suggests that the position of lawyers in society may become increasingly marginalized, reducing social acceptance and leading to lower job satisfaction. Says John Grisham reflecting on his characters in Rainmaker, "In real life you see some lawyers doing some awfully sleazy things trying to get cases, but they're done every day. Lawyers hang out in hospitals. They chase ambulances down to disasters. They do all that stuff, and most lawyers would rather be doing something else altogether." A bizarre example of this marginalization was recently reported in the Economist (July, 1992) which described how a Japanese lawyer tried to rent office space for his firm but was repeatedly refused by landlords when they discovered his profession.

This decline of trust also means that for lawyers in the public arena it will be increasingly difficult for them to sustain their positions of social and political authority. This trend is obvious from the growing numbers of teachers, social workers, doctors and business people - all of whom have higher levels of public trust - among the country's political leadership. "It used to be almost everyone around the Cabinet table was a lawyer," says David Zussman, Director of the Public Policy Forum, "now there are only a handful." In the long run this could invite government intervention into practices which the public views as detrimental. "If the political assumption that governments defer to lawyers changes," says former Ontario Premier Bob Rae, "the profession risks jeopardizing its independence and its freedom to manage and to regulate itself."

In Britain the legal profession was recently surveyed by the Economist which suggested that a growth in lawmaking and regulating activities, together with a de-mystification of the profession and a greater symmetry of legal information has brought to an end to the profession's ability to work behind a curtain of public ignorance -- what Alan Dershowitz has called the profession's "Wizard of OZ syndrome". As lawyers become increasingly more visible, the gap between the ideals of justice, rights and freedoms and the business realities of the law becomes all the more glaring. In trying to maintain a balance between being businessmen and being professionals, the Economist recently concluded that "lawyers have too often failed to find it on their own -- especially where great wads of cash are there to be made".

"Perhaps it's not just lawyers," agrees Rae, "but the law itself which tries to do too much and in so doing loses the public's confidence when the law fails to meet the expectations of those it tries to serve." Due to aggressive media attention, we are witness to a very public decoupling of the Law and fairness, a trend particularly evident in such high profile cases as the Westray mine disaster, the Krever Commission inquiry, and the Holmoka deal, and a trend in which the legal process itself is implicated as an accomplice in heaping harm upon those victims it has professed to serve. It is a system inching towards schizophrenia - outwardly proclaiming justice, promising to establish blame, and to make the guilty pay for their misdeeds, yet inwardly organized to do nothing of the sort while elevating obfuscation to an art form -- with little awareness of the discontinuity perceived by its publics.

Jethro Lieberman once remarked in his 1983 monograph The Litigious Society, that "litigiousness is not a legal but a social phenomenon. It is born of a breakdown in community, a breakdown that exacerbates and is exacerbated by the growth of law. A society that is law saturated inclines toward the belief that in the absence of declared law anything goes. No restraints of common prudence, instinctive morality or reflected ethics need deter or function." In such an environment, one has to ask how fairness, the balance between individual and social rights, is possible? From the outset, the odds are stacked against the public good, and so there is a sort of systemic inevitability that the champions of the legal system fall out of public favour. In today's global economy, Lieberman's warning that "litigation is not an ideal means of building community: its procedures and its impact do much to sow mistrust, and its limited successes may blind us to the need for reforms that lie outside the ceaseless cycle of plaintiff and defendant", is probably even more true.

As the complexity of legal issues grows, so does the need for specialized technical knowledge. "But there is a price to be paid for this specialization," says Conservative Senate Leader and long time lawmaker Lowell Murray. We lose the generalists, the historians, and the scholars, and the profession loses a coherent voice. "I think the Bar Association is pretty timid. It is hopeless to try and get them to come forward and take a clear position. Groups of lawyers take a variety of positions based on specialized areas of interest. When there is a fundamental issue at stake, involving say, the Charter or the rule of law, the Bar has a duty to show leadership." And while lawyers themselves are paid a premium for their specialization, it steals from the profession the opportunity to provide the sage advice that results from broad educational backgrounds, tutelage under common mentors, and a common professional experience. The result is "we are seen as clever at the expense of wisdom," says Rae.

Queen's University professor Hugh Segal reminds us, however, that the lack of public confidence experienced by the profession is not really related to issues of legal competency but to issues of compensation. "In any profession whether it be lawyers, doctors, or teachers in matters of their own compensation there is little trust." As true as this statement is, the huge confidence gap between lawyers on the one hand and doctors and teachers on the other suggests the problem goes much deeper.

While doctors are seen working only for health and teachers working only towards education, lawyers can be seen working for both sides of any legal issue. Therein lies the key problem for the profession, according to Gilles Paquet, Director of the University of Ottawa's new Centre on Governance. "Notwithstanding the presence of moral and ethical individuals within the profession, as a whole, however, the profession is fundamentally mercenary," says Paquet. "It is willing to set aside its morals and ethics for the highest bidder. Legitimacy in this profession is based on process not outcome, and if the process is OK, then the outcome is acceptable, whether or not it is moral, ethical, or just. In no other profession are the anchors of moral and ethical values so shiftable." Paquet suggests that lawyers bear the brunt of a imperfect justice system, one in which the issues of right and wrong end up being as irrelevant as they are meaningless. As necessary as the legal process is for lack of a better alternative, when it reduces truth to what people can be persuaded to believe within the constraints of process and when it relegates truth to a supporting rather than central role, it forfeits its legitimacy in the eyes of a public that has very clear ideas of right and wrong.

It takes a special kind of person to have this kind of moral flexibility. Not everyone can do it, even among those who aspire to the brass ring as a partner in a successful legal firm. In spite of the fact that there may be today as many law students as there are lawyers, a recent Rand Corporation study found that half of all practising lawyers would choose another occupation if they had the chance. Depression among lawyers is higher than among 103 other occupations, according to a John Hopkins study. And to a general public that believes in a reality beyond process, and in a truth beyond equivocation such legal wantonness will always evoke the slick characters of a Grisham novel.

So assuming for a minute that our legal system, imperfect as it is, has evolved as the best of compromises, what does that say about the chances of burnishing the image of the profession? Is the decline in trust irreversible? I for one do not believe so - a belief based not on a poll, not on a book or a news story but on my own direct experience. While sitting across from my lawyer on a snowy day in December I considered our relationship, one built entirely on trust and reputation, and wondered how many other relationships like this might there be. It struck me then that the profession must hold huge reserves of social capital. The challenge therefore seems to be in tapping those reserves and applying them for the public good.

"Ultimately," as Merrilyn Tarlton of the American Bar Association remarks, "the real questions become: What is a lawyer's real purpose? What is the legal profession's ideal role in society? How can the public respect the profession until it can be seen that lawyers express deeply a commitment to public purpose?" These questions go straight to the heart of Lieberman's conundrum -- that the Law is an imperfect tool to help fill the gap in a breakdown of community but that its continued application only further exacerbates that breakdown. If we can conclude anything from this about restoring the profession's image it is that efforts to do so should involve some form of community building, and that they be non-litigious in nature.

Community building is one of three roles played by the Law in society. The Law can be subdivided into three components -- higher, middle, and lower. The higher law deals with social governance, more specifically with facilitating social armistices, designing the foundations of social order, and engineering the rules for future social interactions. The higher law prescribes how we as individuals should live together and as such is a tool of community building. The middle law applies when those community rules break down and therefore has as its focus fairness and redress. The Law here plays the role of referee. Unfortunately, the middle law is often imperfect and sometimes grossly unfair.

The lower law, which resembles a form of medieval combat, specifies certain rules of engagement for parties to legally joust with one another. Given that the rules of community have failed at this point, society allows any activity not proscribed as long as the requisite legal process is adhered to. Here Law assumes the role of litigator and in litigation, the client's need to win tends to subjugate all other concerns, whether they be for ethicalness, fairness and even courtesy. As Jack Freidenthal, Dean of the National Law Centre at George Washington University has described, "those who hire attorneys want their advocates to be street fighters, taking every advantage and giving nothing."

Obviously there is a hierarchy here. If individual behaviour follows the rules of social governance, there is no need for redress. Similarly, if wrongs committed against other community members can be addressed fairly and justly than recourse to legal combat can be greatly reduced. According to Paquet, the growth in litigiousness suggests the higher and middle law are failing to meet the public's expectations for a civil society. The profession thus becomes increasingly sullied by the 'streetfighter' image rather than that of social architect or upholder of justice.

Changing that image requires greater professional attention towards community building -- towards facilitating social compromises; towards designing, or redesigning, forms of relationships appropriate to the emerging global knowledge society; and towards shaping the rules of a new social compact.

While the organized bar has a definite role to play in encouraging lawyers to participate in community building, the task of restoring public confidence can only be effectively assumed by individual lawyers, for it is with them that the social capital resides. To the extent that individual lawyers can foster the growth of trust among their community partners outside the law, to the extent that they can help bridge the divides between the privileged and the disadvantaged, or between individual rights and social obligations, to the extent that individual lawyers can connect disparate elements of society, to that extent they will be successful at refocusing public perception of themselves as sage advisors or community leaders. And as an added bonus, they will simultaneously insure against substitution, for while legal knowledge can always be commoditized, a fiduciary relationship can never be.

As to the organized bar, there is much that they can do to encourage and recognize the values and ethical behaviours exhibited by practising lawyers. And there is much too, they can do to foster a sense of community responsibility among Canadian lawyers. In order to deal with the image problem some suggest an effective media campaign, still others are even dismissive of a fictional issue created by US litigiousness and cultural imports. Such one dimensional thinking for a multi-dimensional issue that involves public perception, public expectations, the role of law in society, and an evolving social context clearly lacks merit. More realistically, however, others have advocated a return to professionalism, or encouraged embracing the new commercialism, or restoring breadth in legal education and recreating legal apprenticeship programs, or enhancing the profession's self-regulatory mechanisms to guard against the excesses of over-billing and unethical conduct. There are, in fact, many approaches the Bar could undertake, but more importantly, the Bar should be vigilant and guard against approaches entirely conceived by lawyers.

The most significant step the Bar could take would be to bring the public into its confidence, both nationally and at local levels, and develop clear lines of open dialogue -- with the community, with business, with the media, with educators, with churches and civic organizations, and with lawmakers. Climbing down from the "ivory tower" may get a little dirty at first, but then trust is not built on initial encounters but a history of reciprocal benefit. "Our challenge is not public relations, it is human relations," says Peter Gerhardt, former Law School Dean and founder of the Institute on the Future of the Legal Profession at Case Western Reserve University.

Peter Donolo, Communications Director for the Prime Minister's Office, is one of those willing to help out. He suggests that the profession "needs to focus on the common good. They should undertake projects aimed at reforming healthcare, at child poverty, and welfare reform, and play off how their expertise can contribute. The Canadian Bar Association could help develop the nascent legal systems of undeveloped or emerging countries. Lawyers need to demonstrate their commitment to the community through 'pro bono' work and the like. The Bar should choose spokespeople to represent those most disenfranchised by the legal system such as women, natives and visible minorities. They should develop a program of responsibility, publicizing role models, making use of snitch lines for legal complaints, and campaigning against over billing and unethical behaviour -- maybe in the same way advertisers do. Above all they need transparency, and avoid at all costs the perception that they are hiding anything, like Air Canada's disastrous handling of a crashed airliner in December."